Life with Goals

Like most professionals, I have been dealing with goals for most of my career. Early on, I was mostly impacted by annual goals. Later, when I got into management, everything started to revolve around quarterly goals.

But those details don’t really matter — the important thing is that almost all of the goals I’ve encountered have been logically dubious, unhelpful, and hurt employee motivation far more than they’ve helped it.

To be blunt, I’m now going to tell you why that was the case, and how to fix it.

Why have goals?

The most obvious reason goals are important is that they set expectations for work, and ideally, set those expectations appropriately so that people do productive things. If goals are set correctly for an individual (or a team of them), that person should know what they need to do to have a positive impact on the organization and get whatever benefits come with that (at a minimum, continued employment, but hopefully more than that).

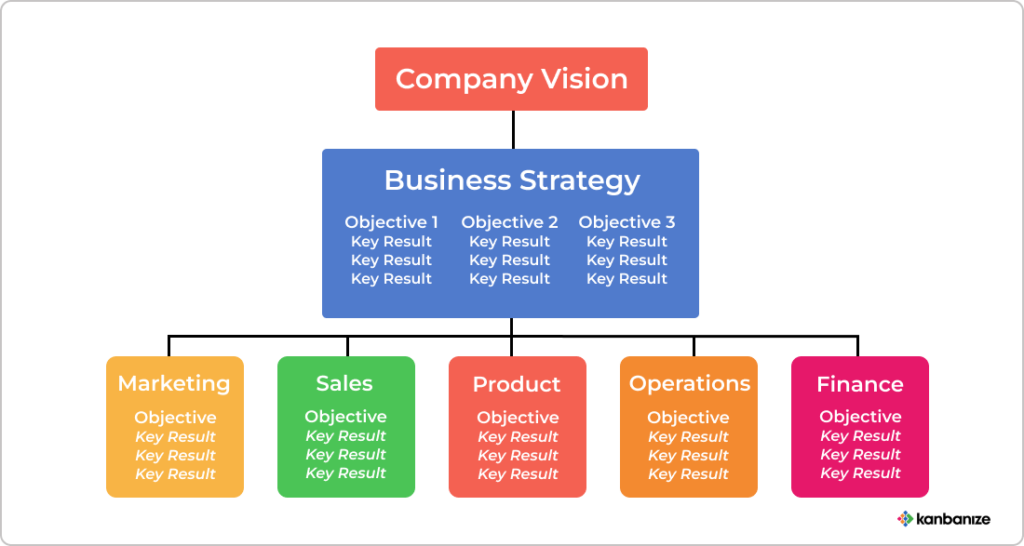

Aside from getting a raise or just not getting fired, goals can/should also link the day to day work of an individual with that of a larger team, and that team with the larger organization. This is so obviously useful — necessary, really — that everyone pretends to do it, but as we’ll discuss later, it almost never REALLY happens for a variety of reasons.

Hitting a thoughtful, realistic stretch goal is incredibly satisfying if it’s connected to both personal success/reward and a larger sense that it’s moving the organization forward in a meaningful, positive way. It gives your work every important kind of purpose.

Why are bad goals so bad?

Nothing says “I don’t care about you or your work” like setting up goals for a person or team (or allowing them to be set by a manager) that don’t convincingly bubble up to the overall company plan.

For instance, if you want to hit $100 million in revenue this year, and part of the plan involves hiring a second lawyer for the company, how are these things connected? If they’re not connected, why are you doing it? Why not hire three more lawyers? Or ten? Or none? And if, deep down, you know they’re connected, but you don’t feel like explaining it because it’s complicated… you’re being a terrible leader! Explaining things is your job! Bad goals are usually lazy goals, or scared goals.

In general, people aren’t going to be happy if they think they’re working for lazy, scared management. But bad goals do more than just fail to point people in the right direction. They often provide a way for people to go in the wrong direction and be rewarded for it!

This just sounds like normal business stuff, why should I worry about it?

The “quiet quitting” thing was a fun little media narrative, but the reality is that paralyzing cynicism at work didn’t start there, and certainly hasn’t abated with a few rounds of buzzy tech layoffs. If anything, it’s worse than ever. Hiring good people is still hard, and having them cynically go through the motions because they don’t believe in their goals is still extremely counter-productive. You can’t avoid it by hiring “better” employees; don’t even think about saying “poor culture fit” right now. The problem is that you are taking good employees — maybe your best ones — and making them less productive or anti-productive by being vague, incoherent, and unaccountable.

If you want people to be “engaged” at work — especially if you are asking them to work hard at things they may not be personally passionate about or even interested in, like dealing with angry customers or cold calling people — you’re going to need to do an excellent job at making their work matter to them. Fortunately, that’s what goals are for. Unfortunately, most leaders and leadership teams make bad goals and bad goals make the problem even worse. You’re probably doing it right now!

Why Your Goals Are Bad

Here are the most common causes of bad goals I’ve seen, based on a combination of my own experiences and those from colleagues.

Problem #1: Goals Are Dishonest

I’ve been in startups for a long time now, and most of the companies I’ve worked for have had — and have made a pretty big deal about, internally — a “mission”. That mission has never (in my experience) been “to make money”, or “to grow revenue at a rate similar to other venture backed companies that were acquired at high investment multiples”. Instead, it was always something very qualitative that seemed more aligned with the interests of the people who started the company, and in most cases many of the people later hired to work there.

For instance, if I worked at a company that made a weather app, their mission might be “to make the world better and more equitably prepared for the impacts of extreme weather”. This would be on the wall, stated in kickoffs, etc., etc. and so forth.

The funny thing is that nowhere that I worked was the ongoing success of this mission actually tracked. Instead, we used the company’s financial and growth goals as an unofficial, unstated proxy for this mission, and we tracked the absolute shit out of those. So when my fictional weather company hit a million dollars in recurring revenue, all the managers would clap and say “we are that much closer to our mission of making a more equitable, prepared world!”

But people aren’t stupid. Even if financial success is a decent proxy in the early days of a simple company, it (very) quickly becomes less so as that company grows and becomes more complex.

Companies like these may have investors who “love” the mission of the company, but what they actually, professionally love is the belief that this mission will cause the company to do things that increase the value of their investment in it, and those things tend to be strictly financial and not necessarily related to the mission at all. Not talking about this doesn’t make it any less true, or any less of a drag on “employee engagement”.

Cynically, my belief continues to be that missions largely exist to pacify employees who may not feel like getting up and putting their hearts and souls into minimizing logo churn, for instance, or building out some annoying single sign on requirement for a giant enterprise account.

But missions are not goals. And we usually pay/promote/hire/fire people based on goals, not missions. When a mission exists (and exist loudly, as it often does), but is clearly deprioritized in favor of increasingly disconnected business performance goals, that mission stops being motivating and starts becoming a cultural AND operational albatross.

Solution #1: Build Better Proxies

If you’re not willing to measure the success of a mission, and celebrate or panic at the results the same way you do when you look at business performance, you should probably dump your mission. That sounds brutal, but I’m telling you, it’s going to do more harm than good before you know it.

Most companies take financial performance seriously, and for good reason! If they perform poorly for long enough, they probably will cease to exist. So financial rigor makes sense, but it also sets that bar for what it means to actually care about something. As mentioned, your employees are not idiots. They can tell the difference between things that are taken seriously, and things that are not, and it has nothing to do with you or a bunch of vice presidents saying “we take this seriously”.

If dumping your mission seems depressing (and it should, so don’t worry), take heart; it’s not crazy to measure your mission. In fact, it’s a good idea! Is there a loose, objective way to measure my fictional weather app’s contribution to a more equitably prepared world? Probably? Here are some random ideas from a non-expert:

- number of people injured in major weather events

- amount of property damage (assuming this could be mitigated with sufficient warning)

- number of weather related car accidents

- something that counts these things across different economic backgrounds and looks for increasing equity there

Maybe these are all stupid, or impractical. What do I know? But then… that just means this is a stupid, impractical mission, and you should either get rid of it or make one you’re serious about. Too many companies treat the vague impenetrableness of their mission as a feature, not a bug. But if you wouldn’t accept that in your financial goals, don’t accept it from your alleged stated purpose for being, because your employees won’t.

Of course, the most logically sound missions effectively tie the two together through a really smart business model where business performance is a highly accurate, believable proxy for mission execution. It’s a high bar, but if you can pull THAT off, you’ll take an enormous bite out of employee cynicism.

Problem #2: Bad Goals Protect Bad Leadership

I don’t meant to be a downer here, but spoiler alert — there’s a lot of executive and middle management that acts in bad faith. These are variable comp leaders (hello!) who would rather be given four incoherent goals they can successfully argue they’ve achieved, versus four clear, logical goals that may have a more direct connection to company success but are more difficult to argue have been achieved when things go badly.

In other words, it’s very hard to create coherent goals when everyone’s personal success relies on some amount of incoherence.

Plus, on top of this fundamental preference for complexity, creating connected goals across multiple functions often requires the leaders of those functions to take ownership of certain assumptions, and frankly, most leaders would rather not do this. For example, go back to my “we want to grow to $100m and also we are hiring a second lawyer” example. The head of the very small Legal team should probably take ownership of the assumption that a second lawyer will help this goal be achieved. Maybe there’s an assumption that fewer deals will be lost to legal obligations, or that contracts will get signed more quickly. Maybe there’s a negative risk — some distraction cost — that another lawyer will mitigate simply by being around.

Those assumptions need to made, and they need to be owned. Now, they don’t need to be owned so that someone can be flogged and terminated if they’re wrong — but how can you get better at making estimates moving forward if nobody actually owns the ones you’re making today?

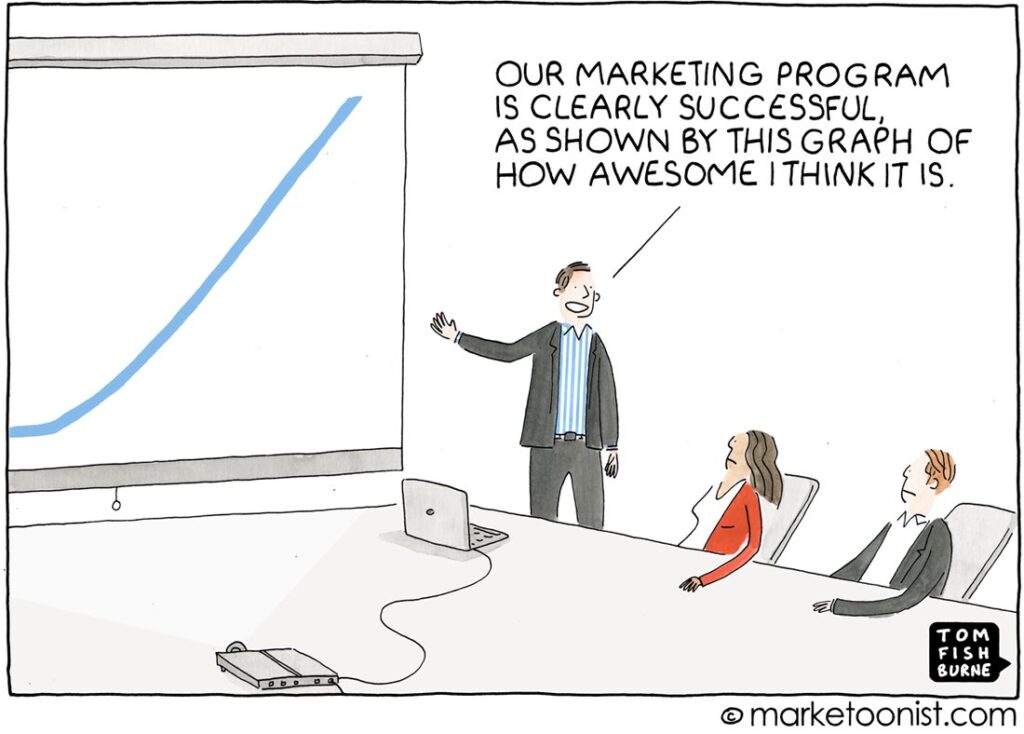

Finally, if there is simply NO quantitative justification for doing something — not even a loose one — somebody needs to say that and defend the fact that despite SO many things being “decided” by data, this thing is somehow fundamentally different. I’m not saying that argument can’t be made, but you have to actually do it if you want to maintain any credibility. Spending a million dollars on PR can’t just “be good for us”, and it can’t just “be time for us to do it”. Clearly we are assuming this has some transactional value (since our company goals are transactional), let’s either take a stab at it, argue for why this thing gets to be vague and unmeasured (which again, is fine), or realize the folly of our ways and do something else.

Solution #2: Own Assumptions and Support the Owners

The fact that there’s a guess or an assumption at the end of a logical rainbow should not be an excuse to simply avoid the rainbow. If/when Marketing hands off “qualified” leads to Sales, there is obviously some assumption of how well those leads are going to perform. Whoever is running Marketing owns that assumption to some degree, as does whoever owns Sales. If the leads are weak, have that argument, and fix that problem. If Sales sucks at closing, same process. But don’t look at each other at the end of the quarter and declare victory from both sides because both of you outperformed some industry average if you look at it the right way.

Similarly, don’t make product goals like “improve onboarding”, list a bunch of deploys, and say the goal was achieved. Hell, don’t even set “improve onboarding” as a goal unless you’re willing to make some assumptions about how improved onboarding can affect the business. And definitely don’t make those without running those assumptions past other relevant departments. If it’s your call, great, but if everyone thinks your assumptions are insane you better be willing to explain why you think you’re right and then get made fun of at the end of the year if you’re wrong.

On the other hand, if you’re thoughtful about it, you also shouldn’t be FIRED at the end of the year for being wrong — that’s exactly why no one wants to own any of these assumptions. Transparency is not the same thing as honesty or good faith, and the latter two are a lot more important than the first thing.

Accountability for my assumptions shouldn’t necessarily be the destruction of my career — it should be that I actually change something I think or do as a result of being demonstrably wrong. Instead, I’ve often seen the opposite on both counts, where no one is willing to take any kind of reputational risk for the good of the larger organization, and as soon as someone does and it doesn’t go their way they’re layered or given the boot in the name of “accountability”.

The great leaders I’ve worked with have used being wrong in controlled, well documented ways as the strongest evidence to do something differently the next time. Unfortunately, too many of them were already gone by the time their knowledge and humility could have been turned into something useful for the company.

Problem #3: One-Way Goals Are Nothing But a Power Struggle

The corporate version of “history is written by the victors” is “goals are set based on the assumptions of whatever department the CEO (or investor, or whomever) is currently enamored with”. In other words, you work backwards from some number, that number is dictated by someone, and thus everyone wants to be that person so they can indirectly control everyone’s goals.

Maybe Finance is in charge. If so, they’ll declare how much money the company needs to make, and everyone will work backwards from that. (This one is at least logical, because in theory they also decide how much money everyone gets to spend.) Maybe Sales is in charge — they’ll set up goals they think they can hit, and whatever they need to hit it (new heads, leads, etc.) will be everyone else’s problem. Marketing leaders often fantasize about being in charge — they rarely are — and creating goals with a clear-eyed assessment of both their perceived value of what’s being sold (which is usually wrong), and resources they have to make people aware of it. Every number is negotiable, except one, and you want to be the person who gets to decide what that magical number measures, and how big it is.

Unfortunately, in this scenario almost everyone is unhappy, frustrated, or checked out. Why? Because no one person or team knows enough about everyone else to set that number on their own. So one function is happy, and the rest are either saddled with numbers they know deep down aren’t achievable (Sales, Marketing, Account Management), or they simply retreat from the numbers and focus on qualitative goals, or completely disconnected metrics that don’t rely on anyone else (Product).

This kind of thinking — as unproductive as it is — works perfectly in a spreadsheet. Something is a number, and everything else is a reaction to that number. The goal is some number, and everything else exists to generate that number.

Here, let me show you what I mean.

Solution #3: Two-Way (or Eight-Way) Goals

If people own their individual numbers instead of having them indirectly dictated to them by people who don’t understand them, you’re much, much, MUCH more likely to set achievable, motivating goals — even if they are still very hard to reach.

So how do you do this? Well, for starters, you don’t make “second class goals”. By that, I mean you don’t have a certain set of numbers that you are willing to take input on, and change, and another set of numbers that are automatically calculated based on others. As soon as you have this two-tiered system in your goals, you’re making certain people’s goals subordinate to others.

This means that while you can use a spreadsheet once you have your goals set, it’s the wrong place to actually figure out what they are. In Resolution, you can set up a model of the business that includes all of the same factors, but makes ALL of them first-class goals. That means all of them can be set, all of them can be changed, and all of them can be temporarily locked once you settle on what something really does need to be.

Here’s what that looks like (you can also click here to try out this model yourself).

Bad goals are worse than no goals

Nobody, in any company I’ve ever worked for, has put enough thought or effort into setting goals well. Maybe it’s because the difficulty of the situation is depressing, or maybe the idea of wrangling consensus out of a room full of egos and insecurities is just too much for all of us to bear.

Well… too bad. Bad, dishonest, hand-wavy goals are making your best employees nuts, and more transactionally, it’s making them leave. No matter how pleasant the unreality of the situation, people are remarkable resilient and determined if you don’t yank them around and send them on the performance equivalence of wild-goose chases.

Be honest. Embrace logic. And don’t complain about silos and lack of collaboration when you refuse to build a single, understandable map of the business that everyone can find themselves on.