CEO Boot Camp, Part One

How big is the opportunity?

Call it TAM, or market size, or whatever you want. The first thing most people will want to know about your idea is how much money is at stake.

The First Question

“What is the potential size of this business” is one of the most basic, fundamental questions that comes up when starting one. You’ll need an answer to figure out a number of important things, but here are just a few:

- how hard/expensive is it going to be to find customers?

- what kind of costs are worth taking on?

- how likely is it that competitors will appear?

- what should my timeline look like?

The answer to all of these things depends on what exactly the opportunity looks like. The good news is that a very basic, high-level understanding of your market is enough to generate some helpful — if imperfect — answers. In this session, that’s exactly what you’ll learn how to do.

Total Addressable Market (TAM)

If you talk to investors or startup veterans, they’ll probably say “TAM” a lot. All this means is “total addressable market”, and it’s just a very common way to talk about how big a potential opportunity is.

Still, TAM is a useful reality check for people with an idea. The “total” part reminds us that it’s a best case scenario, and that even if everything went absolutely perfectly, our business probably wouldn’t capture (or keep) all of it. The “addressable” part forces us to think about (a) whether we can reach certain parts of a market, and (b) whether certain parts will actually want to choose us versus something else, or nothing at all.

Who Is Your Buyer, and What Do They Do?

TAM is usually measured in money, but money ultimately comes from people. That means if you want to figure out TAM, you need to figure out who your buyers are, and how much they’re willing to spend to solve whatever problem you’re solving. Note that for this example, we’re going to talk about buyers like they are individual people, buying individual things. Depending on what you’re selling, you may want to think about individuals, organizations, or some combination of the two. For instance, some software can be sold to “users”, where one individual is one user, but an organization might have a bunch of them, each with an average annual spend.

“We are going to play a really fun game!”

TAM is often discussed as a yearly, recurring amount, so let’s measure it that way here. To do that, you’ll need to take into account how often addressable buyers will pay you. If you’re selling a service, ideally people will continue paying you year after year. If you’re selling a product, think about how long it’ll be before a happy customer buys something else from you, based on how long the product is expected to last. Smoke alarms last a while, sandwiches do not. So if you’re selling cars, obviously most buyers aren’t going to buy a new car every year, so each buyer’s annual contribution to your TAM is less than the price of a car.

The math here is pretty simple, but the attached model will do it for you. You simply take the number of potential buyers, and multiply it by the average annual spend. You can also go backwards, and find out what it would take to have a TAM of say, a billion dollars if you had different amounts of buyers, or different average spends.

Where Do Buyers Come From?

Now that you’ve established how buyers create TAM, it’s time to figure out where these buyers are going to come from. There are a couple of orderly ways to do this, including:

- by industry

- by job title

- by company size

- by current solution

Again, some of these will make more or less sense depending on what your business actually is. If it’s completely out of left field and solves a problem people currently do not solve, or don’t think they have, measuring by current solution usage is a bad idea. Similarly, if your product isn’t inherently useful to large companies, it doesn’t make sense to break down by company size.

The most common ideas tend to disrupt existing spaces, and basically trying to “get a piece” of the market. For that scenario, measuring by current solution works pretty well, so let’s do that.

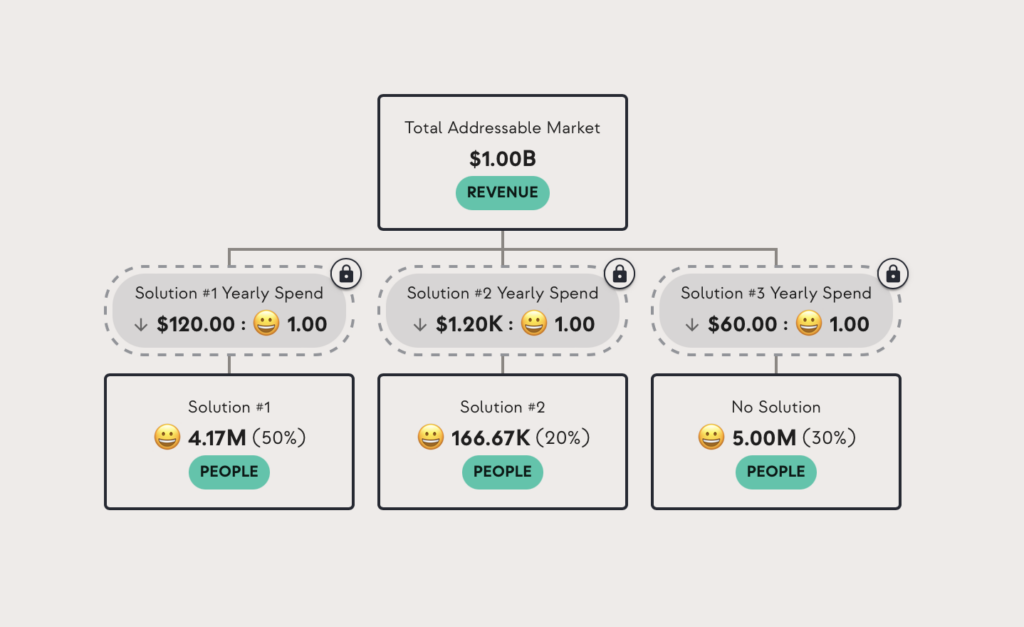

Below we have a simple market breakdown that includes two solutions, and a third option for people who aren’t currently solving the problem (but should). People have different needs, and therefore spend different amounts of money on solving the issue. Solution #1 is relatively simple and cheap (and therefore very popular) but Solution #2 is the right fit for a smaller number of people who can justify the cost.

What about the “No Solution” people? Well, we’re assuming that they currently don’t solve the problem because it’s not worth the cost of even the relatively cheap Solution #1. So they’ve been given a lower value per person with the assumption that at a low enough price, they would be interested in buying.

Simple TAM vs. The Real World

This very simple model lets you play with a couple key concepts that define total addressable market. Mainly:

- The number of people who use different solutions

- The price people have proven willing to pay for different solutions

- How many people who currently don’t buy anything might become buyers, and what price they’d be willing to pay

Believe it or not, this is more diligence than a lot of people do before deciding they have a great idea, or before pitching to investors. It can be easier to simply grab some number from the web (“Food waste is a $68 billion dollar market), but that number alone doesn’t tell you how many buyers there are, what’s different about them, or really anything at all.

So this model is a much better start. But there’s a lot of nuance we may want to add as we consider different factors or learn more about the market.

Additional Market Options

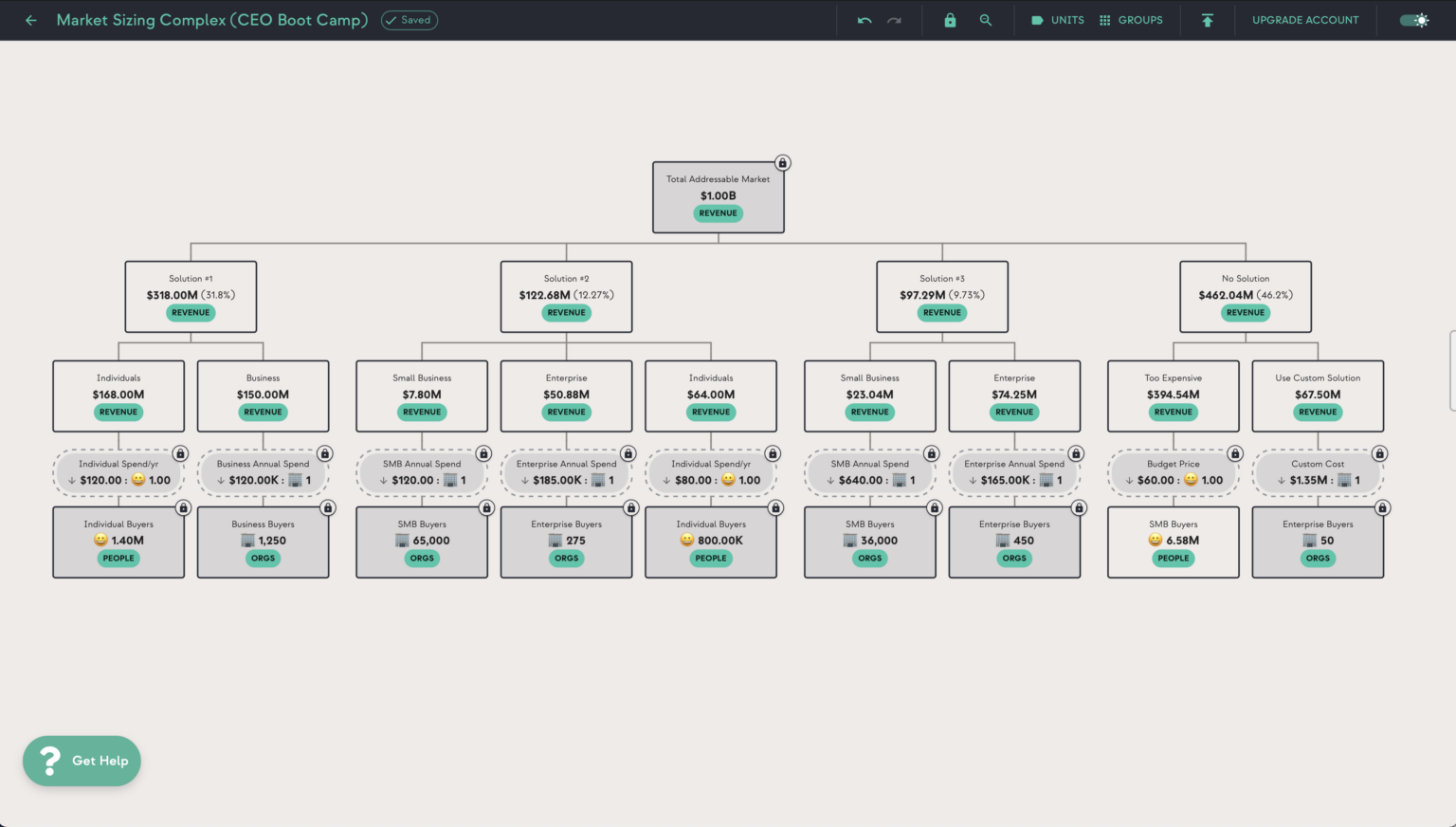

This model only includes two options, but markets often have dozens. In complex enough scenarios, you may even want to group them by category.

Different Buyer Types

Not everyone who buys the same product or service is going to buy the exact same thing. A small company that buys Salesforce, for instance, gets less and pays less than an extremely large one. If the price points are broad enough, you might want to consider them.

Where You Fit In

You can run your business any way you want, but many people struggle when they try to acquire a giant, broad swath of a market like this. Instead, there’s some subset or niche you intend to acquire first. An exercise like this, constructed the right way, can help you figure out the relative size of this group. Once you’ve established the rough market size, you can also lock that number in and see what you’d need to take from everyone else in order to reach your goal.

Here’s a more granular version of the last model with some of these factors added. If you’re ready, make a copy of this model and add any others you think of.

Things to Remember About TAM

TAM is probably the most exciting number you’ll ever work with when figuring out a business, even moreso than things like valuations, because they’re fundamentally optimistic and often enormous. In general, investors seem to be more put off by smaller, conservative TAMs than outrageously humongous ones, although obviously there’s an upper bound to that.

What sounds like an enormous TAM is a necessity when you think about it, though, because it’s essentially the answer to “what is the best conceivable outcome for this idea”. Reality is literally always worse than your TAM, so investors are obviously going to bake that into their opinion of your lofty, rosy TAM number.

However, even if your TAM is ludicrously large, a more granular understanding of how you got it, and how it might change with different assumptions or new information is incredibly valuable when talking it through with people. If you just grab a number off a Google search (or, God forbid, ChatGPT), it’s really easy for someone to say “that number is wrong, because (some random fact)”, and you won’t really have a counter. However, if you’ve done the thinking behind that number, the same objection can turn into a productive discussion versus you hemming and hawing about the quality of whatever third rate PowerPoint you plucked “$3.4 trillion” from.

If you’re not working with investors… congratulations! But TAM is still really useful, especially since if you’re using it to make strategic decisions, you can be a lot more conservative and realistic. You can do a really good job building new products, features, or sales motions and still completely fall on your face if you (a) invest in an opportunity that isn’t big enough to justify it, or (b) put an amount of resources into the issue that is either too big or too small for the moment.

There you go! You now get TAM.